Facing the post-pandemic: ‘We know when something is off with our children’

Showing kids how to talk about feelings is a good first step toward protecting their mental health.

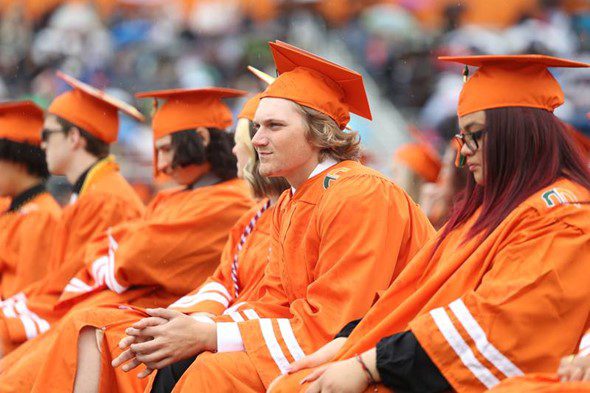

Nothing symbolizes facing a challenging future more than high school graduation. Bryce Atkin sits in attendance on Plainfield East’s Class of 2022 graduation. Saturday, May 21 2022, in Plainfield. Today’s young people must navigate a world where an endemic COVID is their reality. It’s up to adults to prepare them for it. (Gary Middendorf – [email protected]/Gary Middendorf)

Just two years ago, common belief often held that COVID-19 was a temporary blip on life’s radar, that temporary public life shutdowns, or a vaccine, or the right treatments would make the virus go away for good.

Now it appears that COVID-19 is here to stay. The pandemic has become endemic.

How do adults best prepare today’s youth to thrive in that new reality? What if some form of COVID-19 might be in our lives for the long term?

In July 2021, mental health experts from Yale said the way COVID-19 affected kids was unprecedented. Every child was affected, although every child didn’t have the same experience. How kids fared mentally and emotionally was partly dependent on temperament, genetics and family support, Yale mental health experts said.

High school grads this spring walk into a world unlike the one they faced as freshmen.

Also, in July 2021, the return to in-person learning was on the horizon and some felt that the return of routine and normalcy might dispel some of those mental health struggles.

But if 2021 proved anything, it’s that the world did not return to pre-pandemic normal. Mitigations went up and down; guidelines for quarantine and isolation were modified; and new variants appeared – raising new concerns and questions where no one had clear and concise answers.

If adults are struggling to adapt to an uncertain post-pandemic world, how can they help kids feel safe and secure amid all the uncertainty?

But hasn’t the world always been a place of uncertainty?

As far back as 1954, author Mary Reed Newland discussed how parents wrestled with making the world safe for their kids. Newland told the story in her book “We and our Children” about a couple who told their children the family had lots of money in its savings account; so the kids would feel secure.

Except – financial trouble knocked on their door and the couple actually had no bank account.

So what’s the answer?

One “big lesson” people learned from COVID-19 is to talk about mental health more, April A. Balzhiser, counselor and program director at Silver Oaks Behavioral Hospital in New Lenox, said.

April Balzhiser, counselor, is the program director at Silver Oaks Behavioral Hospital in New Lenox.

Balzhiser said people, including children, who struggled with mental health before COVID-19, struggled with it more during COVID-19 – and so did people who never seemed to have had a mental health care in the world.

Yet the more people struggled, the more people talked about mental health and the need for more available and easily accessible resources, she said. So as COVID-19 transitions from pandemic to endemic, it’s important to keep that conversation going, she said.

This is where adults should lead the way, she said.

“We need to have open conversations with our children [about feelings] so that it’s OK and safe to talk about them,” Balzhiser said.

It’s normal for people – kids and adults – to experience many feelings each day, Balzhiser said. When parents are comfortable sharing their feelings, kids can feel comfortable discussing theirs, too, Balzhiser said.

Too often, parents never realize their kids are struggling until a crisis occurs, Balzhiser said. These are not “mean parents” or “bad parents” but parents who simply didn’t know, she said.

That’s partly because mental health concerns in children remain so stigmatized, she said. And partly because of an expectation that once kids returned to their usual routines, their mental health struggles would vanish.

But the return brought its own challenges.

“Kids were being jumped right back into sports and programing at school; they were no longer doing Zoom,” Balzhiser said. “That worked very well with some kids and others struggled with that.”

Students browse the various business booths set up at the Laraway 70C 5th Grade Business Expo. Friday, May 13, 2022, in Joliet. While some kids easily transitioned to remote learning and then back to in-person learning, other students struggled with it, health experts say. (Gary Middendorf – [email protected]/Gary Middendorf)

Nevertheless, kids are resilient across the board, Balzhiser said. But they are also sponges, she said. And they absorb what’s happening around them, she said.

They pick up on their parents’ uncertainty and concern. And it’s OK for parents to say they “had a hard day today” or that they’re feeling stressed, Balzhiser said.

“I think, again, that being able to talk about what we can control, and normalizing that it’s uncertain for everyone, and we work with the things we can do in our day-to-day lives, can lead to much bigger discussions, so it doesn’t become overwhelming,” Balzhiser said.

So what are the signs their kids are struggling with their mental health?

“The best thing is just to trust your gut,” Balzhiser said. “We know when something is off with our children.”

The National Institute of Mental Health offered these signs: frequent tantrums and/or frequent and intense irritability, talking about their fears and worries; frequent stomach aches and headaches with no known medical cause; hyperactive behavior; nightmares, daytime sleepiness; sleeping too little or sleeping a great deal; disinterest in social activities, academic struggles or decline in grades; reacting out of fear.

In addition, teens might engage in risky or self-harming behaviors; drink alcohol, smoke or use drugs; diet or exercise obsessively; believe they are hearing things others do not, feel as if someone is controlling their minds; and have thoughts of suicide, according to the NIMH.

Balzhiser said not to dismiss mood changes in teens as normal adolescent behavior. Encourage teens to talk; ask the hard questions, she said. And take them to a mental health professional if you are concerned, she said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in a 2021 study, 37.1% of high school students experienced poor mental health during the pandemic. And in the 12 months before the survey, 44.2% persistently felt sad or hopeless, 19.9% had seriously considered taking their life, and 9% had actually tried.

“It’s better to be safe than sorry,” Balzhiser said.